Messaging infrastructure

by Tomek Masternak, Szymon PobiegaThe messaging infrastructure is all the components required to exchange messages between parts of the business logic code.

There are two parts to the messaging infrastructure. One is the message broker that manages the message queues (and possibly topics). The other equally important part consists of all the libraries running in the same process as the application logic, that expose the API for processing messages.

Whenever an application wants to send a message, it calls the in-process part of the messaging infrastructure which, in turn, communicates with the out-of-process part. The same process, but in reverse order, happens when a message is received.

Guaranteed delivery

Throughout this article, we are assuming that the message queue we are using is durable and it re-delivers messages for processing in case previous processing attempts have failed. In this model receiving a message is a read operation that has no side effects. In order to remove a message from the queue, it needs to be consumed. The consume operation permanently removes the message from the queue.

Basic operations

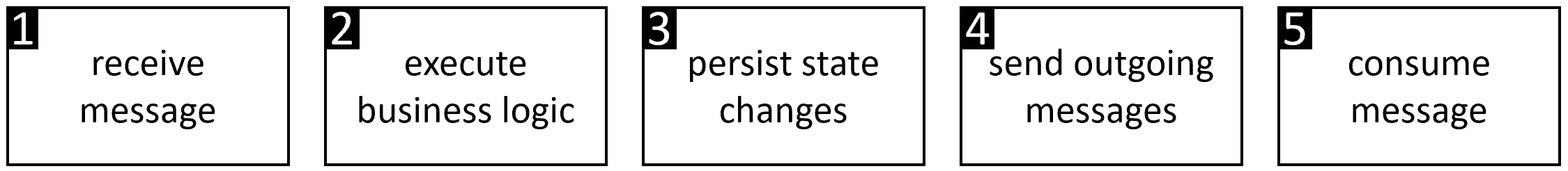

In the model of a distributed system that was introduced in the previous posts, message processing can be broken down into a list of basic operations. Here’s the list in the order that ensures guaranteed delivery mentioned above. - receive message - execute business logic - persist state change - send outgoing messages - consume the received message

Basic operations

Note that in one of the previous posts post we’ve shown how these blocks have a slightly different shape at the system boundary.

Scope of a transaction

If two or more operations are combined into a transaction, it is guaranteed that either all operations complete successfully or neither does. This is the atomicity property of a transaction. Atomicity is not enough, though. We also need to make sure that the results of the transaction are not lost. In other words, we need these transactions to also be durable. That means that an operation can be transactional if it interacts with a medium that can durably record state.

Out of the five operations above, one is non-transactional by nature - execution of the business logic. That might come as a surprise for you at first. Don’t we talk about transactional execution of business logic all the time? Of course, we do but this is a kind of mental shortcut. In reality, the effect of executing business logic is just a bunch of bits flipped in the volatile memory of the computer. Unless that machine has a persistent RAM (which we assume is not the case), execution of business logic cannot take part in a durable atomic transaction.

Consistent messaging

As we mentioned in our first post, the message processing needs to follow a specific pattern in order for the distributed system to be consistent. We called that pattern consistent messaging. Let us now examine possible ways of arranging the basic operations of message processing into transactions such that fit the consistent messaging pattern.

No transactions

The trivial approach is to not use any transactions at all. Each operation is executed in its own context.

No transactions

In this case, we have three distinct failure modes: - business logic has executed - state change has been persisted - outgoing messages have been sent

If we are sending out more than one message, the number of possible failure scenarios increases because sending each message constitutes a separate operation.

This approach requires the least support from the messaging infrastructure but is the hardest one to work with as the business logic needs to take into account all these failure modes and support deterministic behavior during retires. As we showed in consistent messaging this is all but a trivial task even for the simplest business logic.

All-or-nothing

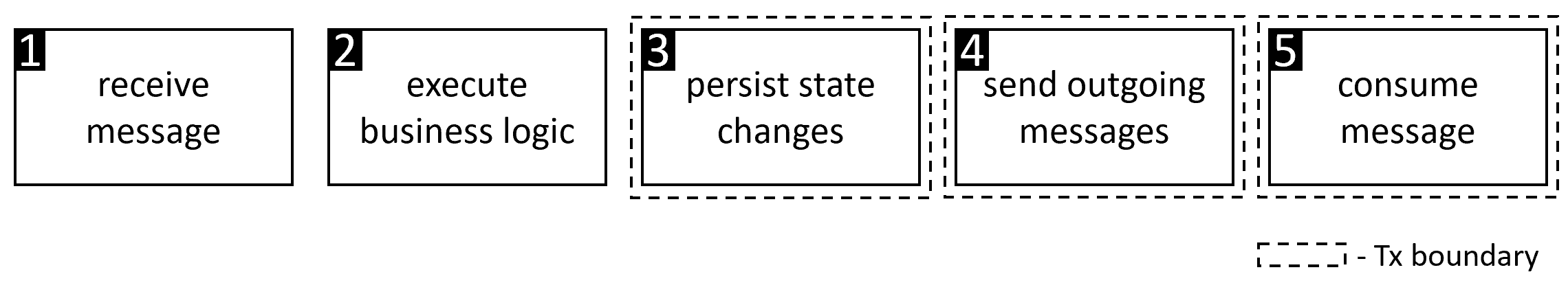

At the opposite end of the spectrum we have the all-or-nothing approach, sometimes referred to as fully-consistent. In this mode, a single atomic and durable transaction spans all the operations excluding execution of the business logic.

All or nothing

The all-or-nothing mode is guaranteed to not generate duplicate messages in the course of the communication as the incoming message is consumed only if the outgoing messages are sent out, and vice versa. So, given there are no duplicate messages, does it mean this is equivalent to exactly-once message delivery? Of course, the answer is no.

The fact that exactly-once message delivery is impossible can be demonstrated using the famous two generals problem 1. In short, the two parties (in our case the messaging infrastructure and the CPU) need to agree what is the state of message processing. This is proven impossible if these two parties don’t share state.

We need to accept that even in the strongest of message processing modes, the all-or-nothing mode, the business logic can be executed multiple times. If a message processing transaction is not completed and the message is delivered again, the business logic is executed as if it was the first attempt. If that business logic produces any side effects, these effects are produced for the second time. An example is calling a web service to authorize a credit card transaction. Each time a message processing is retried, a new authorization is created until the customer’s balance reaches zero. We will deal with cases like this later in the series when we’ll discuss various resources a system can interact with.

The all-or-nothing is a very powerful concept as it allows writing a very simple business logic code. Provided that this code does not produce any side effects, the behavior of the system is exactly as if exactly-once message delivery was a real thing. Sounds compelling, doesn’t it? So how can I use this mode? The all-or-nothing mode can be implemented in two ways.

The first approach is to use distributed transaction technology that ensures that individual transactions against the data store and the message queue are made atomic and durable. The problem is, such technology is no longer widely accessible. Few message queue products support distributed transactions and none of them is designed to work well in the cloud. You can learn more about distributed transactions and the Two-Phase Commit protocol from one of our previous posts.

The second approach is to use a single technology for both storing data and sending messages. In most cases that boils down to emulating a message queue in a database. The drawback of this approach is that databases usually are not designed with the type of workload that is characteristic to message queues, leading to poor performance compared to dedicated message queue solutions. An interesting example of the opposite approach is Kafka where a key-value store can be emulated in a messaging infrastructure to achieve all-or-nothing behavior.

In summary, the all-or-nothing is a great mode due to the simplicity of the business logic code. Despite challenges related to technology, it should be always seriously considered when designing a distributed system.

Atomic store-and-send

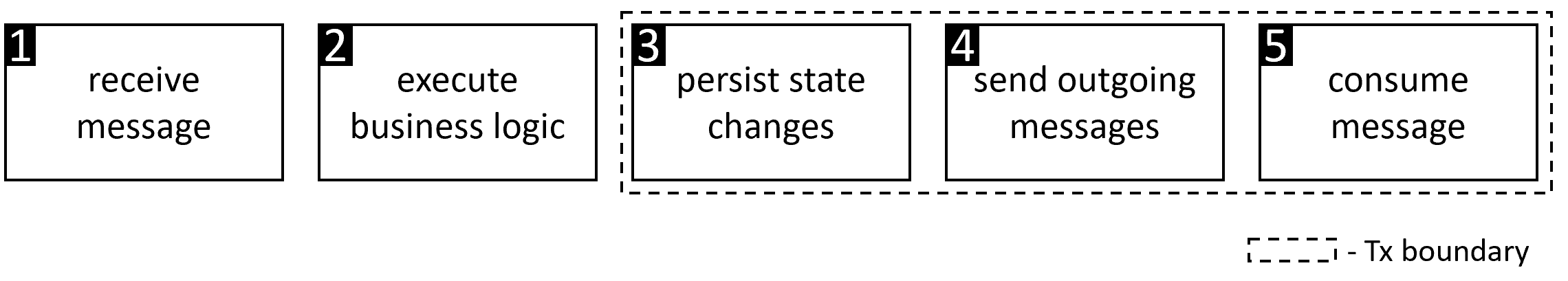

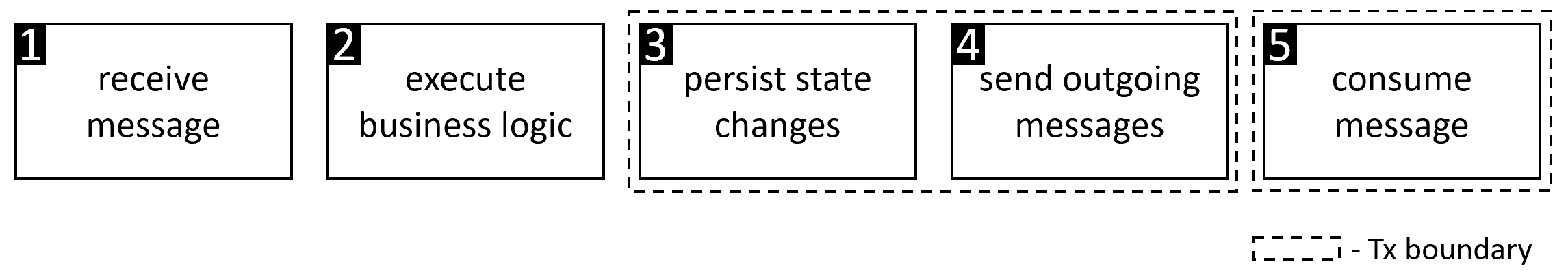

A commonly used middle ground between the two approaches described earlier is a mode called atomic store-and-send or atomic store-and-publish. In this mode, there are two transactions - persist state and send out messages - consume incoming message

Atomic store and send

As a consequence, there is one partial failure mode possible when the state has been persisted and messages sent out but the incoming message has not been consumed. To handle that case the code of the service needs to be able to check if a given message has already been processed.

You might now ask the question: how can we implement a transaction that spans both persisting state and sending out messages? Wouldn’t it require the same sort of infrastructure as the all-or-nothing mode? As it turns out, it does not.

All-or-nothing is equivalent to atomic commit which in general case is harder than consensus problem 2. We need two parties (the database and the queue) to agree on committing the outcome of their respective jobs.

On the other hand, the store-and-send is a much simpler problem of coordinating two operations in such a way that if one succeeds, the other will eventually succeed too. We’ll leave the detailed discussion of that problem to the next post. Here it should be enough to state that storing outgoing messages in the database used for business is one possible solution.

Summary

That was a nice piece of theory but you might ask yourself what’s in it for me. Here’s our suggestion. Choose your messaging infrastructure wisely. Avoid non-transactional infrastructure at all costs as it pushes the responsibility of handling all partial failure modes on the business code. This clearly violates the Single Responsibility Principle is a sure way to cluttered code. Using any message broker directly through its SDK it an example of the non-transactional messaging infrastructure. Really.

The choice between all-or-nothing and atomic store-and-send is a more difficult one. You need to take into account factors such as target deployment environment and expected performance. The good thing is that the decision is not that difficult to change, should the circumstances require it. If you are starting small, we recommend seriously considering all-or-nothing and, only if it is not possible to use atomic store-and-send. Regardless of the decision, remember that business logic does not take part in the transaction and can be executed multiple times. Keep it free of business-relevant side effects (writing log statements is most likely just fine).

One last piece of advice - before deciding to write your own messaging infrastructure code, seriously consider using an existing one. It will save you a lot of hassle. Regardless if you take that advice seriously, stay with us as we explore various aspects of building exactly-once message processing solutions.

Disclaimer

At the time of this writing, the authors work for Particular Software, a company that makes NServiceBus. NServiceBus can be used with various message brokers like MSMQ, RabbitMQ, SQS and others to build messaging infrastructure that can work in either all-or-nothing or store-and-send modes. NServiceBus is not the only product that offers similar capabilities. The authors’ point is not to sell NServiceBus but rather to turn your attention to a general issue.