HTTP protocol for exactly-once processing

by Szymon PobiegaThis article proposes an HTTP-based protocol that can be used to ensure remote invocation is conducted exactly once. It is an adaptation of the token-based-deduplication idea described previously.

One of the most common system integration scenarios is executing a function remotely and fetching the result. It is easy if the target function is pure (does not have any side effects). But what if it does?

The basic building blocks of the HTTP protocol and REST approach are not enough to guarantee exactly-once execution in such a scenario. Let’s remind ourselves what operations we have at our disposal.

Shameless plug – workshops

On May 12-13 we are running an online workshop on reliable message processing. The details on the workhop can be found here. If you like what we publish here, we invite you to join us for the workshop. This time we decided to run it in the Americas time zone so both Europeans and Americans can attend.

HTTP

HTTP defines a set of operations (known as verbs) that help to convey the meaning of a given API call. They also have some specific constraints. The most commonly known and used are GET, POST, PUT and DELETE.

GET is expected to not cause any side effects in the target system. Of course, the implementor of a GET call can be evil and update the database but that would be a violation of the protocol. The reason why GET should not have side effects is the fact that the response to this operation type can be cached so the caller can’t be sure (unless explicitly opts out from caching) if the response comes from the target server or a cache.

Next, there are PUT and DELETE. These operations are expected to have idempotent implementations. This means that the caller should be able to retry calling PUT or DELETE several times and the side effects should be exactly as if they called it once. Again, there is nothing that prevents an evil programmer from violating this protocol assumption. Moreover, there is nothing in the protocol or common HTTP libraries that helps the implementor to comply with the idempotence requirements.

Last but not least, POST carries no idempotency guarantees whatsoever. This is why POST is frequently used when the implementation can’t provide any such guarantees or the service provider could not care enough to provide them.

Traditional solutions to HTTP deduplication

There are two well-known methods of ensuring the operation requested via a HTTP call is performed exactly once.

GET-before-POST

This approach places the entire burden of deduplication on the caller. The caller is supposed to query the state of the service via GET operations to ensure that a given operation it is about to invoke has not yet been invoked. The downside of this approach is that it might be difficult to obtain the necessary information via regular GET calls. It might be necessary to provide a dedicated GET API just for that purpose. Another issue with this approach is the fact that it requires serializing the calls to a given service in order to guarantee correctness. For these reasons, most people choose a different method.

Operation ID

A more popular approach is to add operation ID to each HTTP call that is meant to cause side effects. The operation ID is usually passed as a custom header. The server inspects that header and performs the operation only if it has not been performed yet. Of course to be able to do that it has to maintain the list of all the operations it processed so far. For how long these operation IDs need to be kept? Nobody knows.

HTTP exactly-once protocol

The protocol we propose is heavily influenced by the token-based-deduplication idea described previously and by the AMQP 1.0 protocol support for exactly-once messaging.

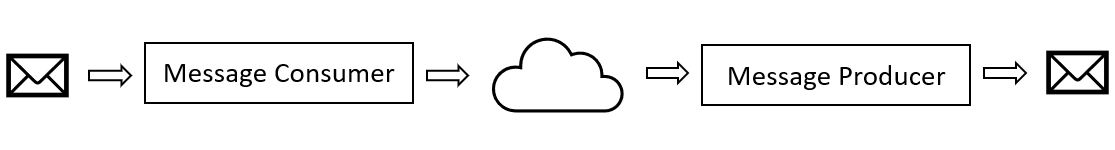

It runs in the context of the side effects handling framework we described recently and assumes that the caller of the HTTP API is a message handler.

Overview

As shown above, the scenario we try to address is an HTTP bridge between two message-driven systems or two parts of a single system. The first question is, how does one invoke the inherently two-stage HTTP API in the context of handling a message? The HTTP interaction consists of preparing and sending the request and receiving and processing the response. Both of these can potentially be associated with a state change of the caller. The problem is that the message deduplication protocols we described so far only allow for one state change transaction per message processed. It looks like calling an HTTP endpoint would require two such changes.

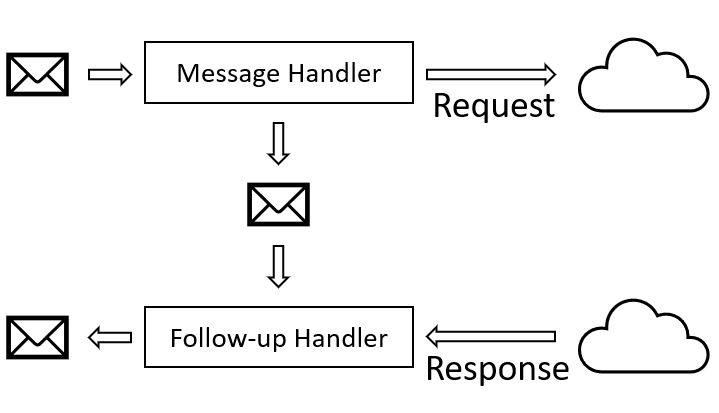

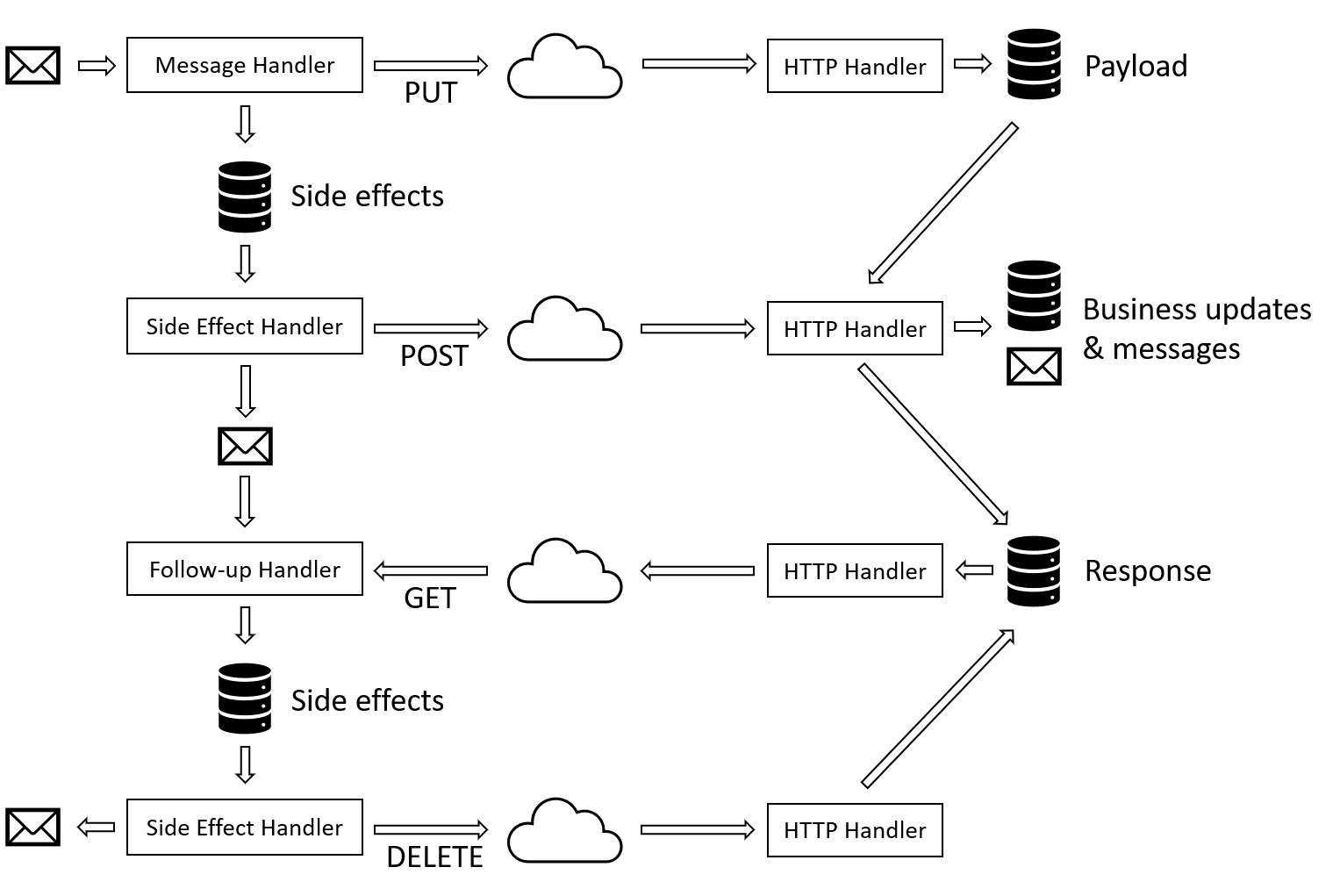

Our proposal is to use a dedicated follow-up message to implement an HTTP call. The initial message comes in and is processed. One side effect of this processing is sending an HTTP request and the other side effect is sending that follow-up message.

When the follow-up message is picked up, the HTTP response is retrieved and made the available as the context for processing. The follow-up message carries the context from the first phase (sending request) to the second phase (processing response).

Two phases

In reality, it becomes slightly more complex as we need to break down the HTTP interaction into four, not two, phases. From the user code perspective, these phases are not visible and implemented as an infrastructural concern. All the user sees is the preparation of a request and processing of the response. The user does not control the verbs used. All they know is that they call the remote service in a way that is guaranteed to be idempotent.

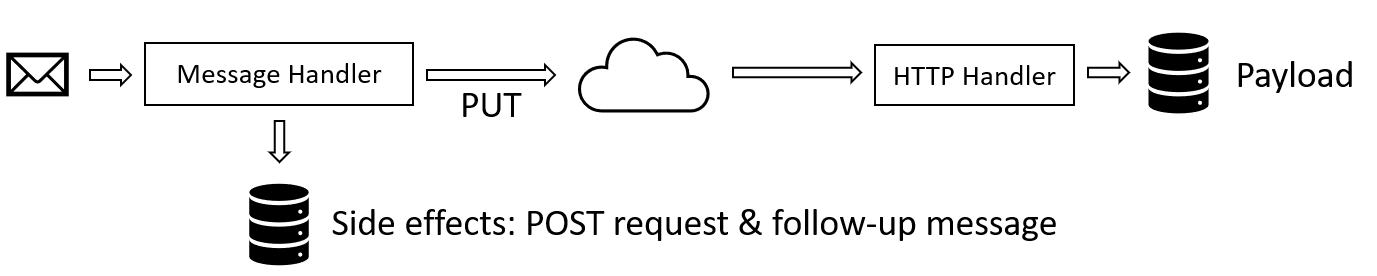

Phase 1 - PUT

The first phase is using PUT to transmit the request payload created by the user code to the remote service. This is done immediately in the message handling code in the same way as creating a blob works (described in the previous post). The cleanup mechanism ensures that requests that are associated with abandoned message processing attempts are removed.

Phase 2 - POST

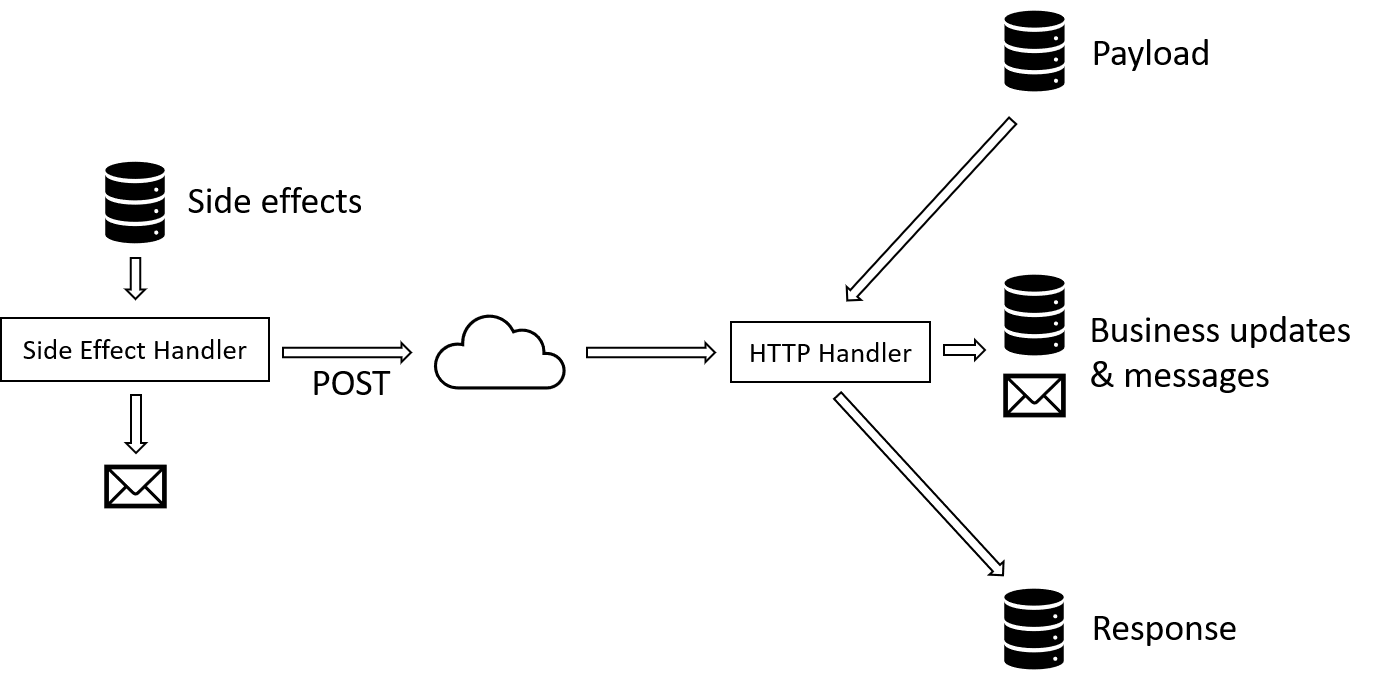

The second phase happens during the side effects publication. In this phase the caller issues POST to the same URL as previous PUT. This is the moment when the target service actually does the processing. The response is not returned directly but stored by the target service in a blob.

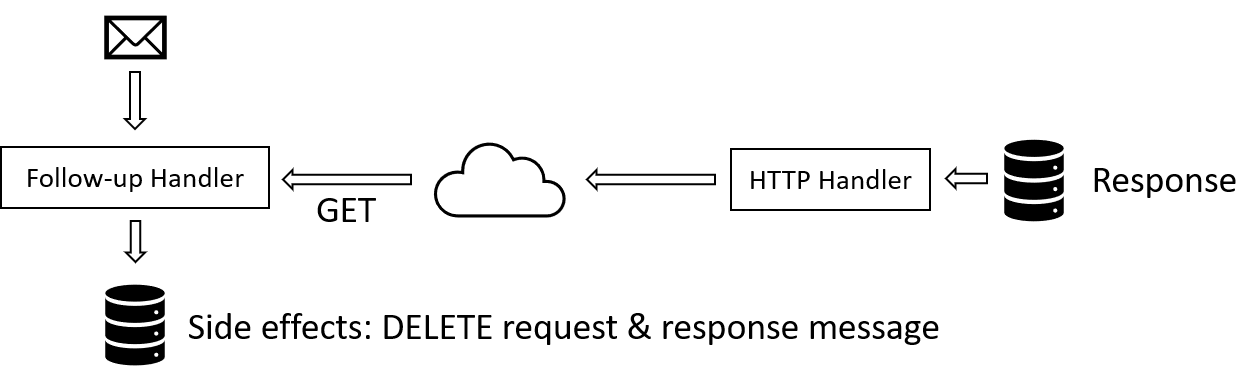

Phase 3 - GET

The third phase happens before the follow-up message is passed to the message handler. The infrastructure issues GET to obtain the response generated in the previous phase. That response is added to the message handling context.

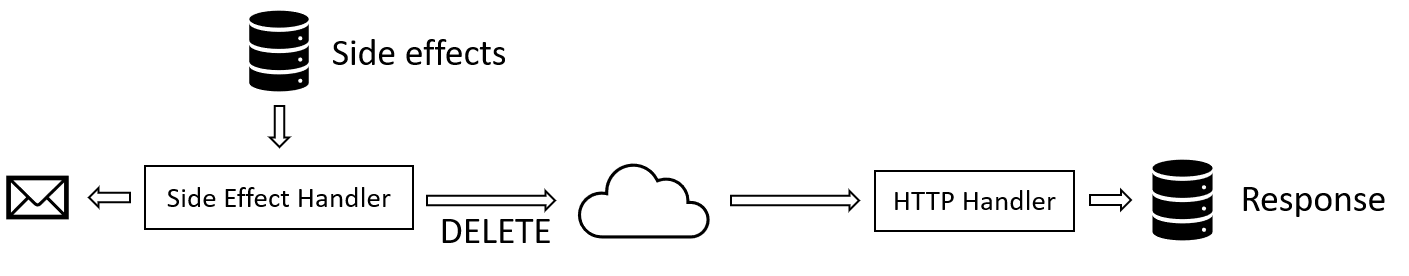

Phase 4 - DELETE

The fourth phase of the HTTP interaction happens during the side effects publication stage of processing the follow-up message. A DELETE is issued removes the response information from the service, making sure that the whole interaction leaves no garbage.

Deduplication

All good but where is the deduplication? You are right, we have just defined how the HTTP interaction looks like in the context of message processing but have not done anything to deduplicate the calls. Well, actually we did. Let’s discuss this by analyzing what can happen in each phase if things go wrong.

If the caller fails after the PUT phase and the message is retried, another request is generated and transmitted via PUT. At the end of the successful attempt all abandoned requests are removed via DELETE. No problem with duplication here.

If the caller fails after the POST phase the same POST will be issued again because it has been persisted as a side effect awaiting publication. This means that the server can receive multiple POST calls for a single request transmitted previously by PUT. How can we deal with that? Careful readers can see an analogy to token-based-deduplication here. The request stored as a blob in the target service is equivalent to a token. It serves as the deduplication state. The implementation of the service marks the request as processed when it executes the POST so that subsequent POSTs are considered duplicates and ignored. In addition to marking the request as processed, the POST also stores the response in a dedicated blob so that it can be retrieved by the caller via GET.

The next phase can be retried any number of times because it only involves the GET to retrieve the already generated response. Finally, the DELETE that removes all information related to the interaction (both the request and the response stored by the service) can also be retried any number of times as deleting a thing is idempotent by definition.

Implementation

We have introduced an HTTP-based protocol for executing operations exactly-once.

The protocol is meant to be used in interactions between message-driven systems. Here’s the code that initiates the HTTP interaction:

public async Task Handle(BillCustomer message, IMessageHandlerContext context)

{

var total = message.Items.Sum(x => x.Value);

var requestBody = new Dictionary<string, string>

{

["CustomerId"] = message.CustomerId,

["Amount"] = total.ToString("F")

};

var content = new FormUrlEncodedContent(requestBody);

await context.InvokeHTTP("http://localhost:57942/payment/authorize/{uniqueId}", content,

new ProcessAuthorizeResponse

{

CustomerId = message.CustomerId,

OrderId = message.OrderId

});

}

It uses simple form encoding to transfer the request. The InvokeHTTP method requires three parameters. The first the URL template for the HTTP endpoint to call. The uniqueId part is a placeholder for the attempt ID required to distinguish between requests transmitted by different processing attempts. The second parameter is the actual request and the third is follow-up message that will be used as a trigger to process the response. Notice that the target service is actually invoked in the side effects publication phase so there is no race condition between sending that message and generating the HTTP response. The latter is guaranteed to be generated by the time the follow-up message is dispatched.

Here’s an example HTTP endpoint for authorizing payments that is the target of the call:

[HttpPost]

[Route("payment/authorize/{transactionId}")]

public async Task<IActionResult> AuthorizePost(string transactionId)

{

var result = await connector.ExecuteTransaction(transactionId,

async payload =>

{

var formReader = new FormReader(payload);

var values = await formReader.ReadFormAsync().ConfigureAwait(false);

var formCollection = new FormCollection(values);

var amount = decimal.Parse(formCollection["Amount"].Single());

var customerId = formCollection["CustomerId"].Single();

return (new AuthorizeRequest

{

CustomerId = customerId,

TransactionId = transactionId,

Amount = amount

}, customerId.Substring(0, 2));

},

async session =>

{

Account account;

account = await session.TransactionContext.Batch()

.ReadItemAsync<Account>(session.Payload.CustomerId);

account.Balance -= session.Payload.Amount;

session.TransactionContext.Batch().UpsertItem(account);

await session.Send(new SettleTransaction

{

AccountNumber = account.Number,

Amount = session.Payload.Amount,

TransactionId = transactionId

});

return new StoredResponse(200, null);

});

if (result.Body != null)

{

Response.Body = result.Body;

}

return StatusCode(result.Code);

}

As you can see, only the POST handler needs to be implemented by the user. The handling for GET, PUT, and DELETE can be part of the framework. With a helper of connector (also part of the framework) the implementation of POST is broken down into two parts. The first part is responsible for parsing the HTTP request data and returning an object that represents it. The second part implements the business logic. The session parameter gives it access to the database (session.TransactionContext.Batch()), to the request object (session.Payload), and messaging (session.Send). Finally, the business logic is expected to return an instance of StoredResponse which allows it to pass both the HTTP status code and, optionally, a payload.

Finally, here is the response processing code:

public Task Handle(ProcessAuthorizeResponse message, IMessageHandlerContext context)

{

var response = context.GetResponse();

if (response.Status == HttpStatusCode.BadRequest) //No funds

{

log.Info("Authorization failed");

return context.Send(new BillingFailed

{

CustomerId = message.CustomerId,

OrderId = message.OrderId

});

}

return context.Send(new BillingSucceeded

{

CustomerId = message.CustomerId,

OrderId = message.OrderId

});

}

As you can see, the response is available via context.GetResponse(). Based on the response the handler can invoke different branches of the business process.

Summary

We have shown that deduplication algorithms that have constant storage requirements are possible. Later we have shown how these algorithms can be generalized to include not only sending of outgoing messages but any time of side effects, such as storing blobs. In this episode, we proposed an extension to the algorithm that allows integrating exactly-once messaging systems via HTTP. You probably know at what we are hinting at now. It is possible and, we believe, it is necessary, to start thinking about end-to-end exactly-once processing guarantees in distributed system design. Distributed transactions are probably not coming back any time soon, we need to get over it. We also need to acknowledge that just make your business logic idempotent is a terrible piece of advice. Keep calm, embrace exactly-once, and dont’t forget about the workshop.