Distributed business processes

by Tomek Masternak, Szymon PobiegaIn the previous post we explained what a messaging infrastructure is. We showed that it is necessarily a distributed thing with parts running in different processes. We’ve seen the trade-offs involved in building the messaging infrastructure and what conditions must be met to guarantee consistent message processing on top of such infrastructure. This time we will explain why it is reasonable to expect that most line-of-business systems require a messaging infrastructure.

Architecture is not an exact science

There are two types of architects out there. There are ones that will tell you exactly what patterns and technologies you should use even before you have a chance to explain what is the problem your system is solving. There are also ones that will tell you either “it depends” or “your mileage may vary” even if you have given them the exact specification of the application. That says a lot.

Software architecture is not an exact science. There are hardly any rules backed by solid research. Most of it boils down to which conference you have attended recently. But do not despair. It turns out that if you look under the buzzword-ridden surface, there are concepts out there that can be studied with more rigor.

State change

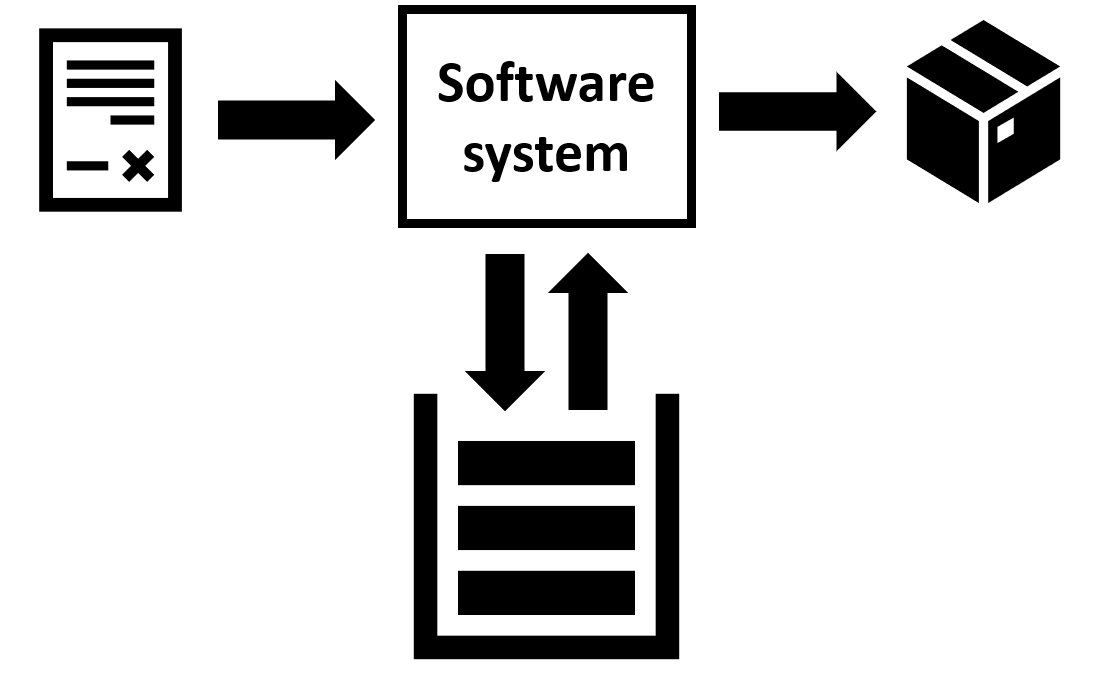

The most fundamental thing in line-of-business software is a state change. State changes are the very reason we build such software. A system reacts to real-world events by changing its internal state - when you click “submit” an order entity is created. Conversely, a state change of the system triggers an event in the real world - when order state changes to “payment succeeded” the parcel is dispatched to the courier.

Software system

Chains of state changes

A system as described above consists of a single data store and a single processing component. That is not how modern software systems are built. Regardless of your approach to architecture, the system is, sooner or later, going to consist of multiple components. One common thing that we can identify in such a system are chains of state changes, one change triggering another.

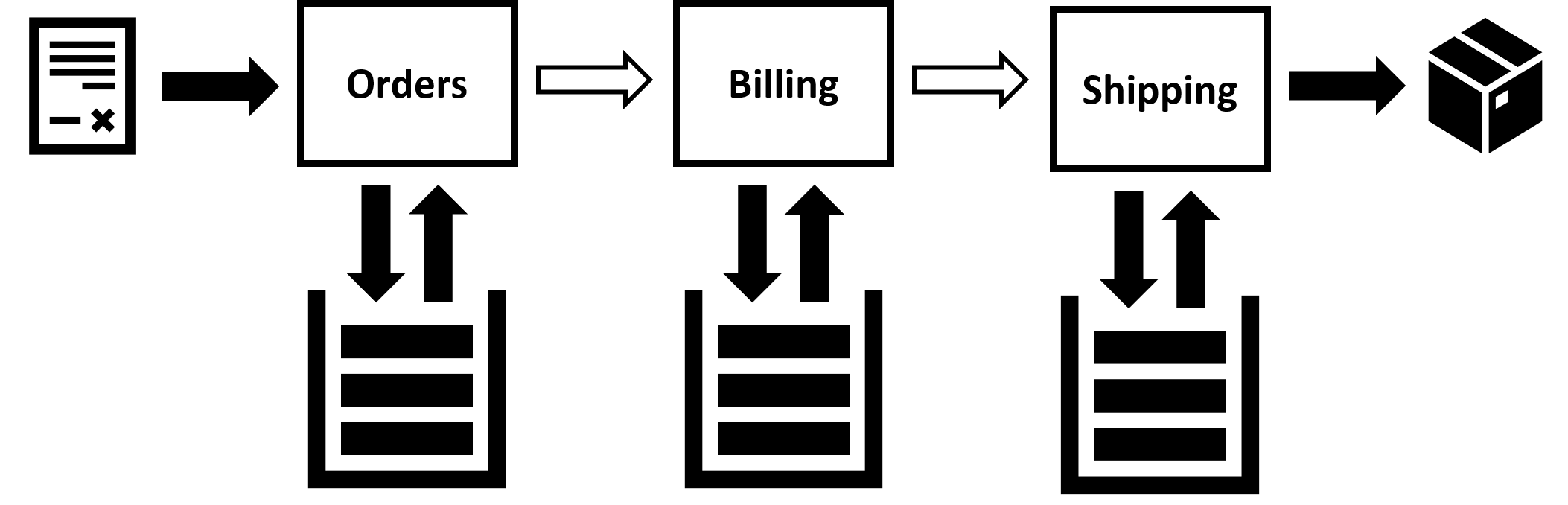

Chains of state changes

When you click “submit”, the order and shipment entities are created. When the payment succeeds the order entity is modified. But that’s not enough to get your new phone delivered to your door. When the order state is set to “payment succeeded”, the shipment entity has to be modified too to trigger the delivery. One state change causes another state change, possibly in another part of the system.

Distributed business processes

We call these chains of state changes, one triggering another, distributed business processes. You can find them in most line-of-business systems. They are interesting because they are independent of the architectural approach taken.

Looking at the distributed business processes more formally, we can describe them using the following statements: - if the initial change has been persisted, the follow-up changes will eventually be persisted too - for each instance of initial state change, the follow-up state change has to occur exactly once - the follow-up step is only triggered after the initial step has been durably persisted

A necessary element of each distributed business process is communication. The fact that the initial state change has occurred needs to be communicated to the code that executes the follow-up change. Let’s see what is required for such communication.

Reliability

We want the communication to be reliable to make sure that the message triggering the follow-up change is not lost.

De-duplication

We want the messages that trigger the follow-up change to be de-duplicated in such a way that if the follow-up change is already persisted, receiving another copy of the trigger message has no effect.

Causal order

We want the message that triggers the follow-up change to not be delivered before the initial state change is durably persisted.

Consistent messaging

We mentioned consistent messaging before

we want an endpoint to produce observable side-effects equivalent to some execution in which each logical message gets processed exactly-once. Equivalent meaning that it’s indistinguishable from the perspective of any other endpoint.

Now we can see that this definition is not enough to guarantee robust and non-confusing distributed business process execution. We need causal order and reliable delivery in addition to the above. That translates to an additional clause:

if message processing includes state changes and sending out messages, the state changes should be visible to the outside observer before messages get sent.

Idempotence is not enough

It is a common misconception that idempotence, as a property of a persistence code, is all that is required to build distributed systems. Well, not when distributed business processes are considered. Let’s assume that the operation that applies a state change is idempotent. That means it can be applied multiple times and the side effects (in this case the state of the data) is the same as if it was applied only once.

We will now use that idempotent state change operation in our message handler. The handler is receiving messages and sending out messages to trigger the follow-up state change.

The handler receives a message and invokes the idempotent state change operation. Now we should send out a message that informs about the state change. But what state change? We don’t know if any state change occurred as part of this execution. All we know is the current state is exactly as if the change occurred exactly once. The only message we can send would carry the current state. Such a message is useless as far as distributed business processes are concerned because it cannot trigger any follow-up changes. The distributed business process cannot continue.

Layered model

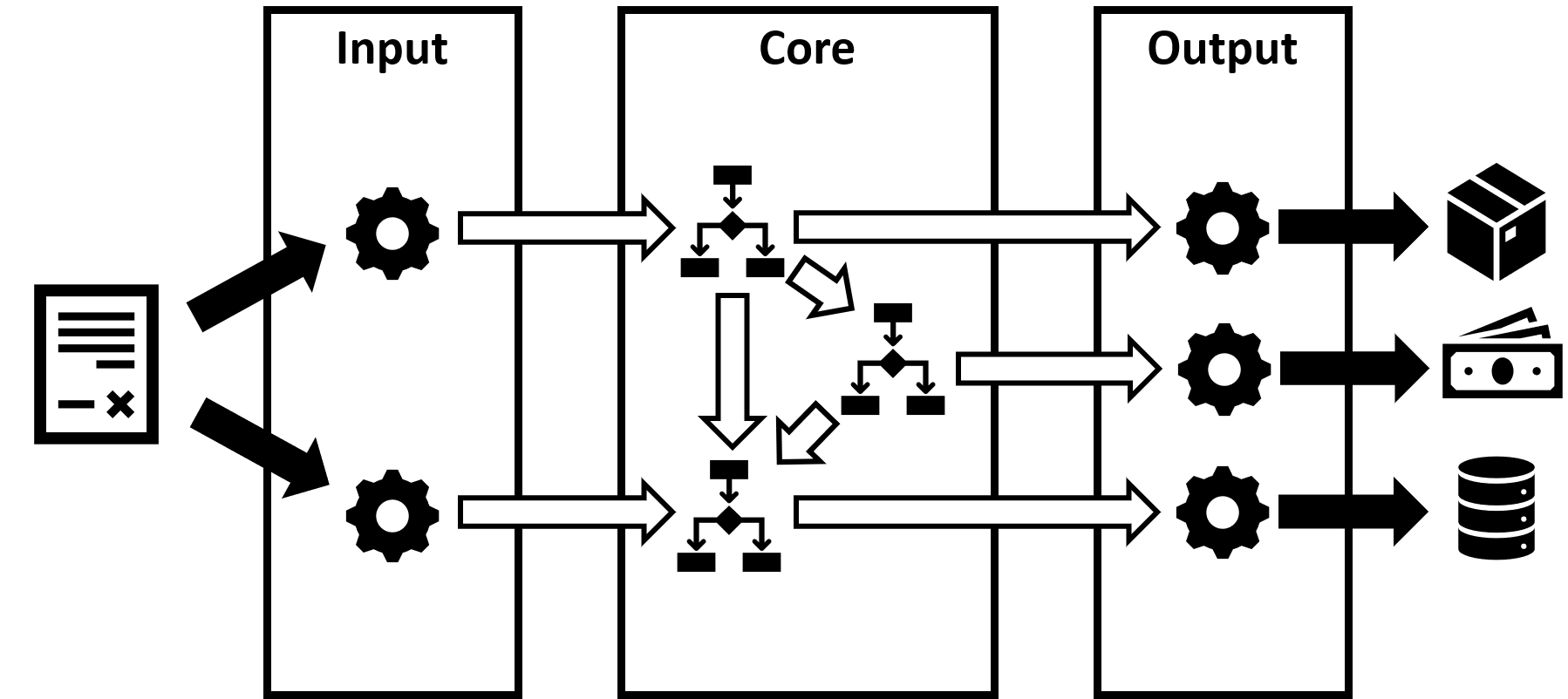

Based on the above one can create a model of a distributed system that consists of three layers.

Layers

The first layer is the input layer. It consists of components that handle synchronous communication with the external world. The famous shopping basket component fits here.

Next up is the core layer. Between the input and the core layers, there is the sync-async boundary. Components sitting at the boundary generate async messages compatible with consistent messaging rules based on the data captured in the input layer. The core layer consists of message handlers capable of communicating according to the rules of consistent messaging. Distributed business processes such as the order handling process or shipping process live here.

The third layer is the output layer, consisting of message handlers that are merely idempotent. Although their logic handles duplicate messages correctly, they are not able to emit messages that could trigger follow-up state transitions. You might find here a message handler that processes an InvoiceRequested event and generates a PDF document to be stored in the Blob Storage. If the triggering message gets duplicated, the handler will generate another copy of the PDF document but will detect duplication when attempting to store a new blob. You might also find here a handler that processes AuthorizeCreditCard commands and calls external payment API. Because such a handler takes the PaymentId field of the incoming message and sends as TransactionReference to the payment provider, that provider can correctly de-duplicate calls. In this model messages always flow left-to-right between the layers. Inter-layer messages are only allowed in the core layer.

Can you fit your distributed system into this model? We would like to hear your opinions. Challenge us on Twitter!